Highlights

- US small cap stocks need a combination of Federal Reserve interest rate cuts and a resilient economy to outperform their larger counterparts.

- Small cap stocks aren’t as cheap as naive valuation measures suggest, but they still sell at a moderate discount to large caps.

- We like small caps vs. large caps in the US, as an upside play in a global stock market in which high potential returns are getting harder to come by.

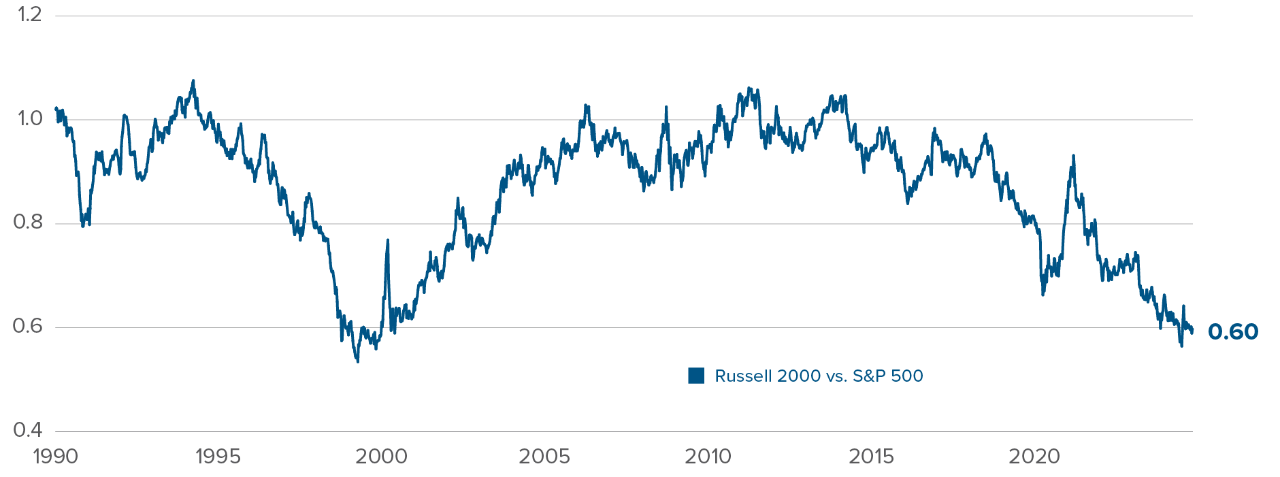

No one will be surprised to learn that small capitalization stocks have had a rough decade, especially in the US. Small caps had a fleeting moment in the sun in late 2020, when unprofitable levered companies rallied on the hopes of a vaccine-driven recovery and access to cheap financing conditions. But since then, they’ve consistently underperformed large cap stocks, save for a quick burst this past July, amid whispers of a Federal Reserve (Fed) pivot towards lower rates.

David losing against Goliath in US markets

Total return ratio, Russell 2000 vs. S&P 500

Source: Bloomberg. Total return ratio index set to 1.0 on January 1, 1990.

Source: Bloomberg. Total return ratio index set to 1.0 on January 1, 1990.

The July melt-up does offer a recipe for small cap outperformance. In the early part of the summer, US economic data quickly moderated from red hot to “normal”. Inflation approached 2%, job creation reverted to historical norms and forward-looking indicators inched down across the board. Markets began front running an “all’s well that ends well” resolution to the post-Covid inflation turmoil. Rate cut expectations for 2024 rose from one to four in the span of a few weeks. These macro developments explain much of the 12% Russell 2000 rally in July.

Going forward, the window for small-cap outperformance is narrow: multiple Fed rate cuts, but without a serious deterioration in the economy. Rate relief is paramount, with small caps having higher debt loads and shorter borrowing terms than large caps. Because large non-financial US corporations termed out their borrowing in 2020-2021, large cap debt service didn’t rise much when the Fed hiked aggressively in 2022-2023. Some mega-cap companies’ earnings even got a windfall from holding significant interest-bearing cash on their balance sheets throughout this period of rising rates. Small caps, funded through bank loans and private credit, were more negatively exposed to shifts in interest rates.

Small-cap balance sheets begging for lower rates

Proportion of balance sheet debt maturing before and after 2026

Source: Bloomberg.

Source: Bloomberg.

Historically, small caps outperform large caps in the year following the first cut of a Fed normalization cycle. With the skewed debt distribution highlighted above, rate relief might be even more crucial this time around. But if they’re accompanied by a recession, rate cuts would be cold comfort for small caps. Four-tenths of Russell 2000 companies are currently unprofitable. While that number is inflated by the smallest of the small stocks, a recession could wipe out a chunk of the index.

Over coming quarters, a bet on small caps is partly a bet on a soft landing. As we covered in our September commentary, the moderation in economic indicators we saw over the summer is more than just noise. We’re far from an outright contraction in growth — especially after the September jobs day upside surprise — but we think that, absent policy easing, the emerging moderation would snowball into a contraction. However, the pre-emptive 0.5% cut in September strengthened our conviction that the Fed would be reactive enough to cushion the US economy’s landing.

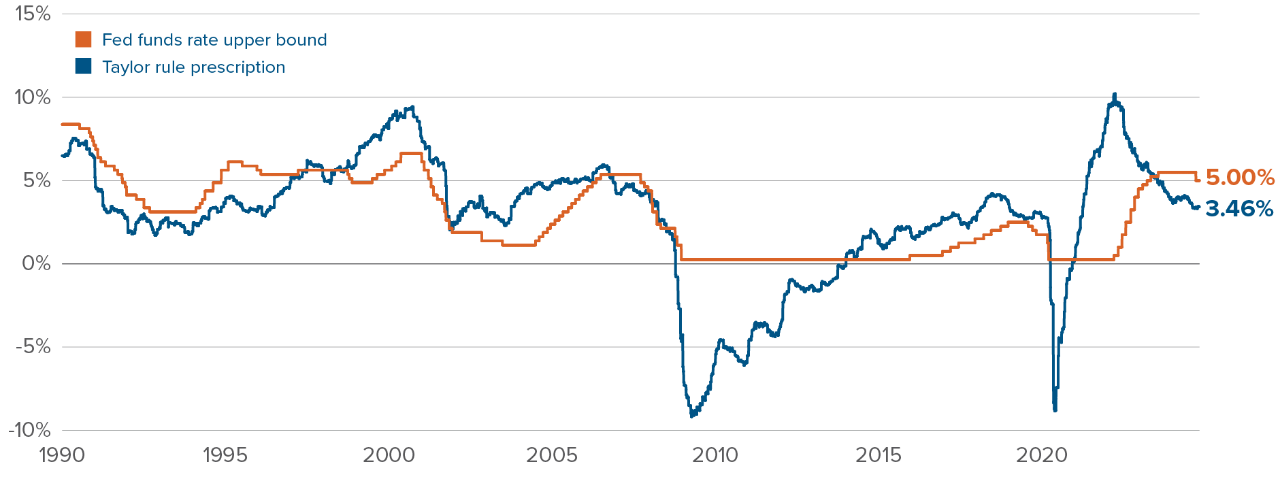

The state of the US economy warrants rate cuts, but we’re far from an emergency. Our real-time Taylor rule, which bakes in the average economic forecasters’ 12-month-ahead views on growth and inflation, is prescribing a policy lending rate around 3.5%. We expect the Fed rate to reach that level in mid-2025, with the Fed tempering its cut size from 0.5% to 0.25% going forward.

Rates are too high, but there’s no emergency to cut

Real-time Taylor rule prescription

Source: Calculations by the Multi-Asset Strategies Team.

Source: Calculations by the Multi-Asset Strategies Team.

The probability of a small-cap rally over the next few months depends partly on macroeconomic outcomes; the scale of that rally depends on valuations. Naive valuation measures, like aggregate price earnings ratios, suggest that small caps are much cheaper than similar non-recessionary periods in the past two decades. But aggregate measures ignore the difference in sector weights between small and large cap indices. While the weight of tech-adjacent companies in the S&P 500 has ballooned over the past decades, it has decreased in the Russell 2000. Partly because successful tech companies graduated from small to large caps as the sector outperformed, partly because of the equal-weighting methodology of the Russell 2000 index. Hence, a portion of the historical “small vs. large” discount is due to sector differences. But we should expect tech-adjacent companies to have pricier valuation than, say, energy or financial companies, given their prospects for long-term earnings growth.

S&P 500’s domination by tech-adjacent stocks is distorting comparisons with other indices

Share of tech-adjacent stocks in indices

Source: Bloomberg. The “tech-adjacent” super-sector is defined as the sum of Information Technology, Consumer Discretionary, and Communication Services (Telecommunications in the case of the Russell 2000).

Source: Bloomberg. The “tech-adjacent” super-sector is defined as the sum of Information Technology, Consumer Discretionary, and Communication Services (Telecommunications in the case of the Russell 2000).

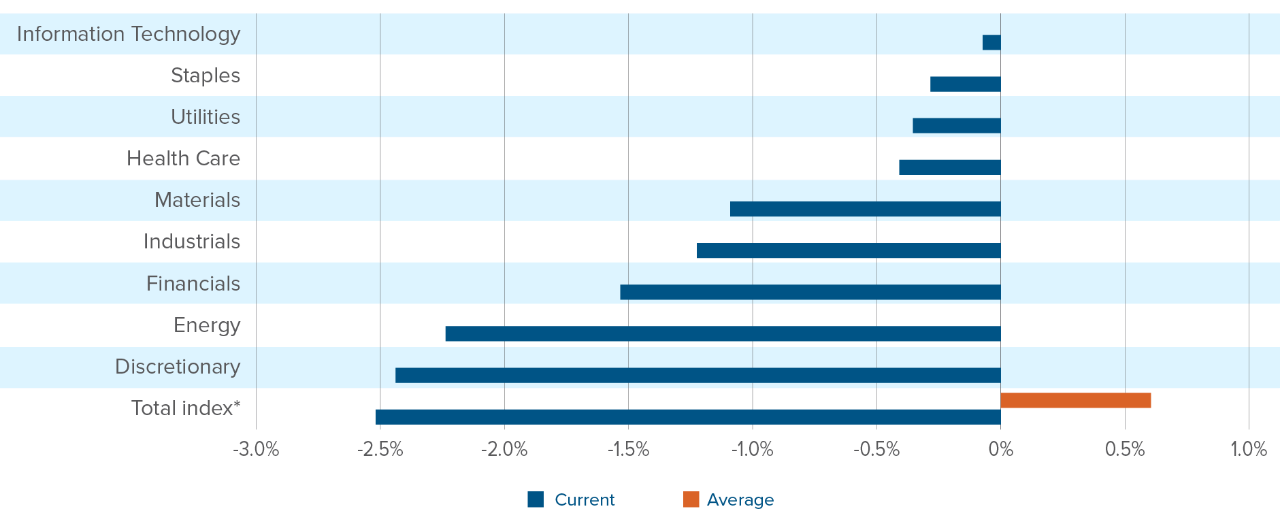

Once we adjust for sector exposures, small cap stocks aren’t historically cheap, but they do sell at a moderate discount to large caps. The chart below shows that while sector-by-sector discounts in the Russell 2000 vs. S&P 500 are not as large as the valuation discount in the overall index — partly due to the sector mix issue highlighted above — no Russell 2000 sector is more expensive than the equivalent S&P 500 sector. Looking at the chart below, Russell 2000 sectors range from similarly expensive (Information technology) to much cheaper (Consumer discretionary and Energy).

Moderate small cap discount across sectors

Positive earnings yield, S&P 500 minus Russell 2000, today vs. average

Source: Bloomberg. The chart compares the positive earnings yield from continuing operations on the S&P 500 and Russell 2000 indices, by sector, and overall. *The historical data for the total index relative valuation starts in 1995.

Source: Bloomberg. The chart compares the positive earnings yield from continuing operations on the S&P 500 and Russell 2000 indices, by sector, and overall. *The historical data for the total index relative valuation starts in 1995.

In our view, the biggest risk to equities for the coming year is simple gravity weighing on returns. It is not economic in nature. We expect US growth to remain solid, global ex-US growth to rebound and central banks to keep slowly cutting rates around the world — all tailwinds for global earnings. But even amid this promising economic backdrop, pricy valuations will act as a drag on returns. The cure for high prices is low prices: we prefer pivoting to cheaper corners of the global stock universe, whether it be international markets or small caps in the US. Small caps are not a bargain, but they do offer across-sector discounts relative to large caps. And if the Fed manages to squeeze through the narrow soft-landing window, the valuation gap between small and large caps could close quickly.

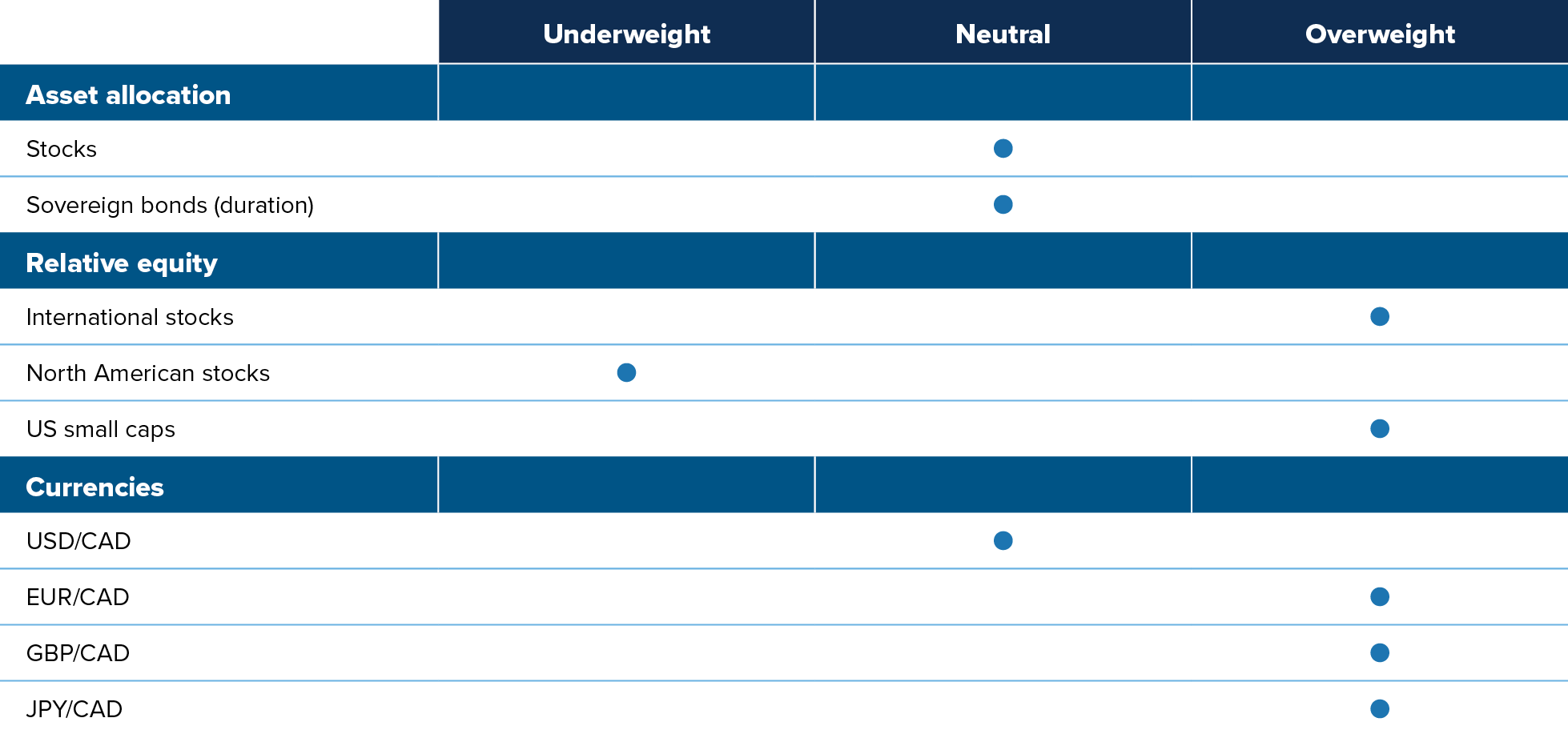

Multi-Asset Strategies Team’s investment views

Tactical summary

Note: The views expressed in this piece apply to products that are actively managed by the Multi-Asset Strategies Team.

Positioning highlights

Turning neutral on duration: We’ve mostly shied away from duration over the past few years. We preferred leaning into stocks for returns and saw US recession odds as overblown. We still don’t expect a recession anytime soon, given the US government’s continuing deficits and the Fed’s eagerness to cut rates ahead of a contraction. But we also don’t see high risks of an inflation surge over the next few quarters, the ultimate risk for fixed income. Accordingly, we’re comfortable taking a roughly neutral position.

Still not ready to bet against equities: While global stock markets are clearly expensive, valuations are not at extremes, like they were, for example, in end-2021. Investor positioning is supportive in the medium term, and we expect the US to avoid a recession as a slew of rate cuts help stabilize the economy. This leaves us with a broadly neutral view on global equities.

Overvalued North American stocks: We generally don’t like North American stocks, whether Canada or US, relative to other opportunities worldwide. Not only do international stocks generally have more attractive valuations than North American assets, but they should also benefit from promising macro catalysts ahead. China’s economy is stabilizing, if not bouncing. European, and, to a lesser extent Japanese, stocks benefit from a macro stabilization of China.

Upside potential in small caps: Small cap stocks are not a bargain, but they are somewhat cheaper than large cap stocks across sectors. Small caps’ window of outperformance is narrow: it requires both Fed rate cuts and a resilient US economy. But if the post-Covid economic overheating does resolve with a soft landing, the valuation gap between small and large cap could close quickly.

Canadian landing: The macro situation in Canada is much more dire than in the US. The Canadian economy has an argument for the most disappointing advanced economy year-to-date. The job market is deteriorating quickly, especially when adjusting for working population growth and government hiring. We like Canadian government bonds, but dislike Canadian stocks and the Canadian dollar, especially against currencies other than the US dollar.

Commodity-exporting EM currencies: Commodity-exporting EMs are well situated to outperform in this macro environment. Their budgetary and external balances have improved amid high global nominal growth and high commodity prices. Their central banks started raising rates much earlier than the rest of the world. As a result, they have generally reached the end of their tightening cycle, reducing the risk of overtightening into a recession. But the level of rates remains high, offering positive carry over most other currencies. On the other hand, we hold a negative view on the currencies of Asian EM countries. Their external positions have severely deteriorated, and their interest rates are relatively low. Thailand’s prospects have improved significantly, but Korea and the Philippines are still stuck in the macro mud.

Doubling down on European duration: Inflation rates have been pulling back in a synchronized manner across euro area countries. In recent weeks, even solid-but-unimpressive economic indicator prints have been met with rallies in long-term rates, as markets price out the right tail scenario of an inflation spiral. At the other end of the spectrum, United Kingdom and Australian duration are less attractive.